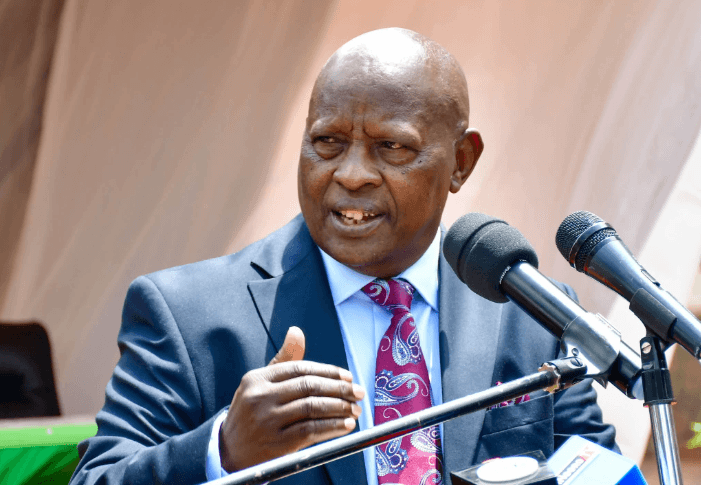

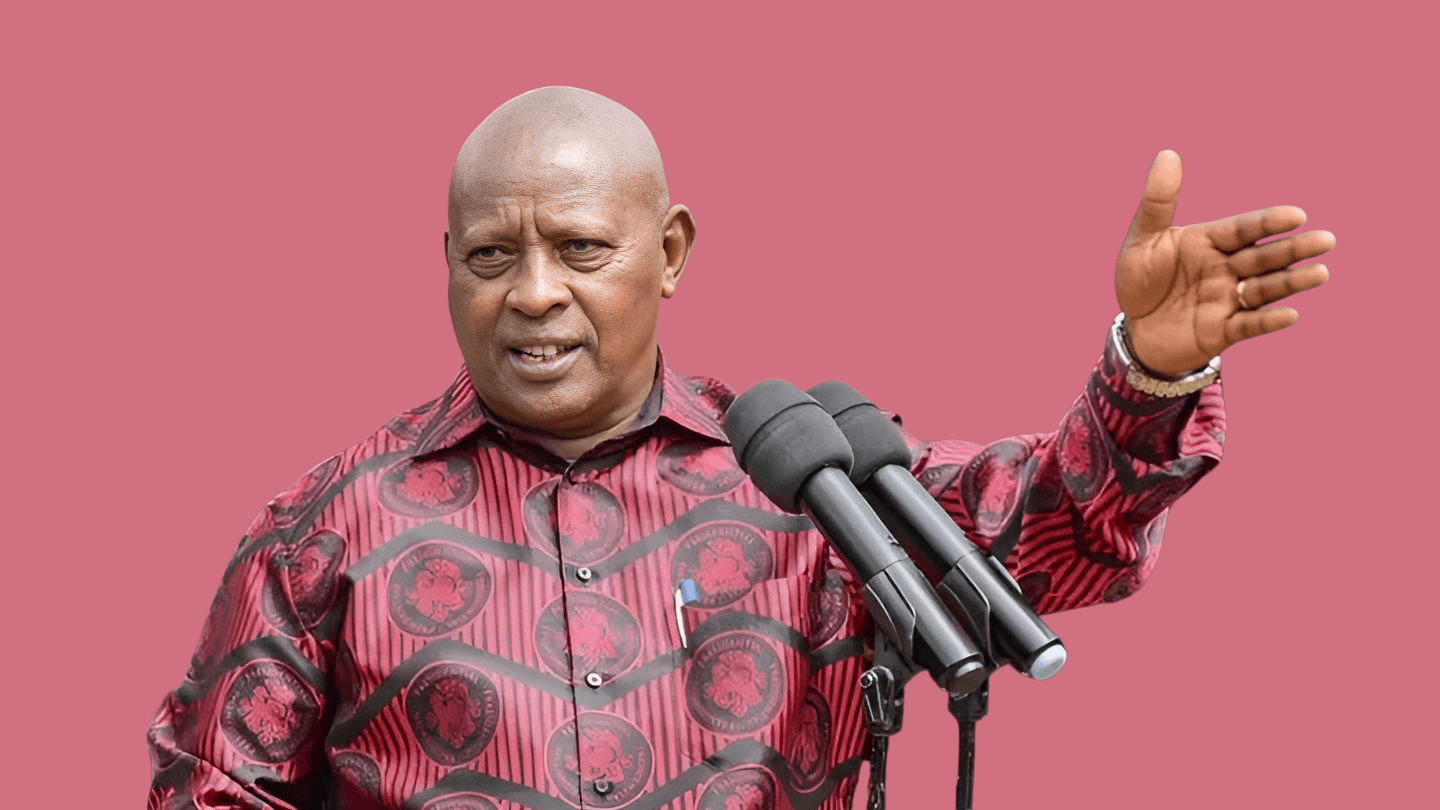

“When you look at me, how do I look? Like a disturbed person?”

That’s how chief government pathologist Johansen Oduor responds when asked the inevitable question: Why does he work on the dead? Isn't he disturbed?

Based on the nature of his job, some people might expect him to look strange. But that is not the case.

To him dead bodies are harmless. When they are alone, they don’t move. They won’t hurt you.

Oduor has become a household name across the country.

He is usually on television briefing the media about postmortem results in controversial deaths.

One that can be easily remembered is the murder last month of university student Rita Wean who was strangled, decapitated and dismembered. The severed head was later found in Kiambu county.

The government pathologist opened up to the Star about his profession and how how manages it alongside his daily life.

Oduor was raised in Mlango Kubwa, one of the Nairobi's informal settlements in Mathare area. His dream from childhood was to be a doctor.

It was a dream many doubted he could attain, coming from a poor family.

“When growing up I wanted to be a doctor and that is something even in high school I would tell everyone,” he said.

“By the way, I went to a day school in Nairobi in Eastlands where I would walk in the morning for kilometres to school and go back home to Mulango Kubwa. That’s where I grew up, so you can see where I come from, hardship. And, of course, I wanted to be doctor but people didn’t believe it could happen,” he said.

While growing up he noticed that whenever some people died, there would be unconvincing reports about how they died.

In some cases, different pathologists issued contradicting reports, making it hard for courts to give sound decisions.

Because he was smart, determined and had the grades, he made it to medical school.

It was while studying a number of medical courses that he realised there was a gap in pathology.

Besides, watching of crime scene investigations on TV roused his interest to do even better.

But studying medicine was far more nerve-racking than Oduor had fantasised.

“When you are in your 20s, perhaps 21 years old, you are told this is an anatomy lab. This body is yours for two years to dissect. That is the time you get through all those mental problems," he said.

“You have anguish but you realise that you need to pass exams. You told your father you will be a doctor, so can you quit in first year? So, you find that with time it is part of you and by the time you become a pathologist, it is just work.”

He said dealing with mass casualties has made him accustomed to his work of handling body after body.

Each autopsy in its own unique way is always a learning experience for him. Casualties from the Garissa University terror attack, the West Gate raid, the Dusit2 attack were all different.

By the time Oduor was facing the Shakahola exhumations in Kilif last year, the past incidents had a cumulative, and probably dulling, effect ton hiim.

“When I became a pathologist at first I didn’t know I could get in the middle of such things. There have been other mass casualty incidents that I have managed,” he said.

He describes how he found himself in the vast Shakahola forest in Kilifi for his latest big assignment.

Speaking to delegates attending the 14th Kenya Medical Research Institute Scientific and Health Conference in Nairobi, Oduor said it all begun on March 22 last year when the office of the government pathologist received a notification from the Directorate of Criminal Investigations.

The notification requested exhumation of bodies of two children who had been buried in a shallow grave at Shakahola after starving to death due to extreme religious practices.

The DCI had applied to the magistrate’s court in Malindi, which issued an order for exhumation.

“When you look at the order, it was known that it was only two children who had been buried but when we went there, we found that they were not just two children. There were actually so many people and it now required serious planning with a multidisciplinary team,” Oduor said.

Based on the initial exhumation order, only three pathologists went to Shakahola hoping they would be done within three days.

But on getting to the burial site, they discovered that there were mass graves.

To date, at least 429 bodies have been found. The investigators return to Shakahola next month for more digging and to bury the bodies that have been positively identified.

Oduor said that just like any other human being, he sometimes gets emotional but specialists in counselling always help, as was the case in Shakahola.

“When you are in these situations, of course, you can get emotional also but we have specialists who deal with such because as in Shakahola we used to go for debriefing every evening. After finishing, we would go for debriefing and it helped so much,” he said.

When he is not at work, Oduor spends his free time reading or hanging out with friends.

“I read a lot and I don’t think there is any day that I don’t read, so most of my time is spent reading. But, of course, I sit with friends in social places. I like music a lot. I like travelling also, so I also do things just the way you do your hobbies,” he said.