The principle of state monopoly of violence, advocated by the late German sociologist, Max Weber, presupposes that the state’s security forces will operate lawfully under a legitimate civilian authority, where actors conduct themselves in accordance with democratic norms and principles of good governance.

The unspoken gist of the principle being that the small number of security officers presiding over the much larger population, can only do so with the latter’s consent, the withdrawal of this consent then becoming a clear path to anarchy.

I am reminded of this by the ongoing saga of abductions that have occurred in this country over the course of the past year, becoming more brazen and prevalent towards the end of 2024.

The Kenya police have consistently claimed that they are not involved in the kidnappings, but you would be quite foolish to imagine that any other group of people can be driving around carrying rifles, grabbing civilians from their houses and the from the streets, while using vehicles with fake registration plates.

But what if the police chain of command is right, and it really doesn’t know which security organ is conducting these abductions?

This is where the first unintended consequence of the abductions would be.

Traditionally, trained security professionals frown on shadowy security units, especially those that work on the whims of politicians, running rings around their turf.

Imagine for a moment the police, one day, genuinely responding to a live session of one of these kidnappings and ending up in a shootout with heavily armed abductors who turn out to be fellow security officers.

Besides, the resentment so created, within the larger formal security apparatus, by certain sections of the security services working outside the chains of command, has the effect of lowering morale and commitment for those of them who stick to the rules of the game.

Which begs the question; if the security services need to arrest anyone, why are they not doing so in broad daylight and using known units? What is all this fuss around kidnaps and dramatic arrests of perceived suspects?

What, however, worries one the most, is how, with each kidnap, the security services, if they are behind this, manage to unwittingly raise public anger against the government.

In fact, it doesn’t even matter who is doing it, because if it is not the police or other agencies, the next big question is why they are unable to stop the kidnaps.

But before we absolve them, we are alive to the testimony of previous kidnap victims, which all confirmed that these were the works of the police and other state organs. We have to return to Max Weber briefly at this juncture.

We have already been made aware that the state control of the instruments of violence by a small number of security officers hinges on the consent of the larger populace to be ruled by this small, selected number.

Essentially therefore, no government is immune to the ability of the citizens to rise up against this monopoly of state violence, once it is clear that it has been misused or abused by the wielders of power.

Perhaps this would be a good enough point for the Kenya Kwanza regime to introduce its security units to the Weberian philosophy of management.

Admittedly, the new generation of anti-government protesters is characterised as young, almost faceless, social media users with rather unorthodox ways.

My generation, far removed socio-culturally and politically from the modern one, would never have, for instance, countenanced the act of posting manipulated pictures showing living leaders and public figures in caskets, regardless of political differences.

But times have changed, and we must acknowledge that the methods of governance have to change too, to go with the times.

I do not think for one moment that a government or president whose hold on the security forces is total, would live in fear of pictures of leaders appearing in caskets.

If anything, the high handed nature of responses to the young artists engaged in this simply encourages, as we have seen, more and more young people to join in on “the fun”.

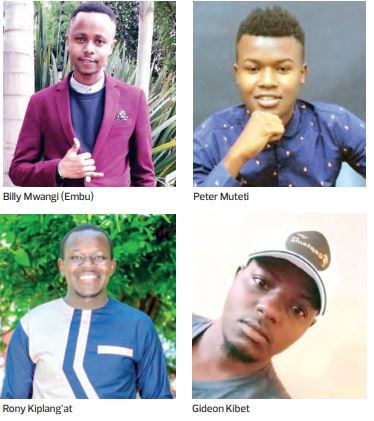

Soon after the kidnapping of silhouette cartoonist, one Kibet Bull, social media was awash with fresh pictures showing the president in “funeral mode”, a challenge to the authorities to arrest them all if it dared to.

It should be clear to the government and the police that the description of balaclava-donning, gun-totting people driving unmarked cars or vehicles with fake registration plates, is exactly that of gangsters.

If indeed security officers are part of this, they are unwisely creating a gap in which gangsters can reign, while presumed to be the police.

Conversely, this also encourages citizen vigilante action, for in the fullness of time, when the populace comes to accept that the abductors are not the police, nothing stops them seeking to protect themselves from further infringement by shadowy characters.

There has been a worrying but marked rise in what I would describe as “presidential hate” directed at President Ruto, since the impeachment of his former deputy, Rigathi Gachagua, I dare say, there is even a deeply tribal angle to it, because the agitation against the Kenya Kwanza regime has been increasing in the Mount Kenya region.

I have opined here numerous times before, that the best way for a government to respond to citizen anger is to deliver, so that a larger part of the population can cite development by the state to counter the anger in sections of the population.

In other words, a high-handed response to citizen agitation is a luxury that a government grappling with rising national anger can’t afford.

Even where it becomes obvious that the impeached deputy is fuelling a large part of the disenchantment for his own political survival, President Ruto surely has enough political muscle to respond to Gachagua using political methods, rather than having shadowy security units running around trying to instil fear in the masses.

After all, there is only so far, in terms of sustenance, that fear factor can take a government, before citizens overcome it.

I don’t know how much advice President Ruto takes from his intelligence and national security apparatus. But I am hoping that among them are people he respects enough to tell him that “these abductions won’t end well”.

Police and security reforms have been some of the longest and most delicate endeavours in this country.

We already reached a point where DCI officers could finally just text a “compel to appear” notices if they wanted to interrogate someone, a far cry from the past, when they would storm in to occasion an arrest in the crudest manner.

There is a disturbing level of misuse of state resources in the tracking, kidnapping and holding of suspects, before being released without charge.

In all of these abductions, where a crime is perceived to have been committed and the security services are interested in interviewing the subject, a “compel to appear” notice would suffice.

The drama around abductions is primitive, and useless, in so far as it aims to create fear, while managing to do only the opposite.

State security must surely know by now that rogue units only accelerate the fall of regimes, because they ultimately unite the people in their hunger for freedom from these characters!

Stop the abductions!