In light of the recent court ruling regarding the stipends for junior healthcare workers in Kenya, I feel compelled to express my concern.

As a medical professional, though not a legal expert, I am moved to question the implications of this judgment for our healthcare community, particularly those just beginning their careers in an already challenging field.

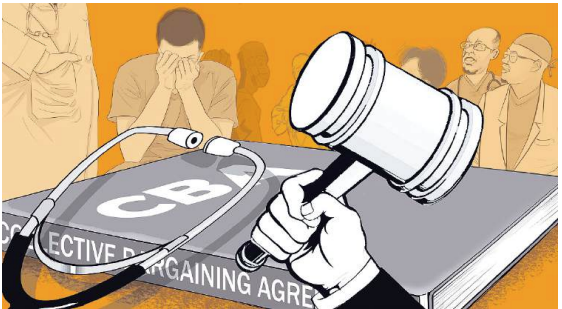

The Employment and Labour Relations Court recently dismissed petitions challenging the Salaries and Remuneration Commission’s advisory, which effectively reduced the stipends for healthcare interns.

This decision came despite the existence of a legally binding Collective Bargaining Agreement that promised higher stipend—terms that had been sanctioned by the court itself.

Yet, rather than upholding this agreement, the court directed that the terms be subject to renegotiation.

A CBA is not a mere recommendation; it is a contract legally binding all parties involved.

According to Section 59 of the Labour Relations Act, “a collective agreement binds for the period of the agreement all parties to the agreement.”

This provision underscores that once a CBA is signed and registered, it has the force of law, with terms that are enforceable just like any other contract.

By directing a renegotiation of this CBA without the mutual agreement of both signatories—the Kenya Medical Practitioners, Dentists and Pharmacists Union and the Ministry of Health—the court’s ruling effectively undermines the very essence of contract law: pacta sunt servanda (agreements must be kept).

Furthermore, the ruling risks eroding the trust that junior healthcare workers place in the legal processes designed to protect their rights.

If a legally binding agreement like a CBA can be adjusted without their consent, what assurance do they have that future agreements will be respected?

It sets a troubling precedent, not just for healthcare workers, but for any group that engages in collective bargaining.

The Constitution of Kenya, in Article 41, enshrines the right of every worker to fair labour practices, including the right to engage in collective bargaining.

This right is intended to protect workers’ interests, ensuring they can negotiate terms of employment in good faith and trust that these terms will be honoured.

By directing renegotiation, the court’s ruling seems to disregard the protections enshrined in Article 41.

This move could be interpreted as a step backward for labour rights, suggesting that the collective agreements workers rely upon for their livelihoods can be subject to unilateral changes.

The role of the judiciary is to interpret and enforce contracts, not to modify their terms or mandate renegotiation unless there is a clear basis for doing so—such as illegality or unconstitutionality.

In the case of National Bank of Kenya Ltd. vs. Pipeplastic Samkolit (K) Ltd. & Another [2001] KLR 112, the Court of Appeal emphasised that “it is not the function of a court of law to rewrite a contract between parties.”

This precedent underlines that the terms of a legally registered CBA should be respected and enforced as they are, unless all parties agree to modify them.

The ELRC’s directive, by contrast, appears to overstep this boundary, altering the expectations set by the CBA.

By directing the renegotiation of a registered agreement, the court has blurred the line between enforcing the law and altering contractual terms.

This creates uncertainty not just for the healthcare sector but for all industries where collective agreements play a role in setting employment standards.

For junior healthcare workers who are already working under strenuous conditions, this uncertainty further compounds the challenges they face.

The right to collective bargaining is not only a national legal standard but also an international labour standard.

Kenya is a signatory to International Labour Organisation Convention No 98 on the Right to Organise and Collective Bargaining, which mandates that “workers shall enjoy adequate protection against acts of anti-union discrimination in respect of their employment.”

The ILO emphasises CBAs are integral to

maintaining fair labour practices and should be

respected as a means of promoting industrial peace

and stability.

© The Star 2024. All rights reserved

© The Star 2024. All rights reserved