President William Ruto’s officiating at the anniversary celebrations of the Ol Pejeta Conservancy last weekend was a reminder of just how important such conservancies are for the preservation of Kenyan wildlife, as well as the growth of Kenyan tourism.

Having been an observer of the Kenyan tourism sectors for many years now, I am aware that official government policy in this sector has been largely focused on increasing tourism numbers.

And the holy grail of Kenyan tourism was we must in some way “catch up” with South Africa, which after all, had much the same natural attractions as we did, only they seemed to be making better use of their natural attractions and conference facilities.

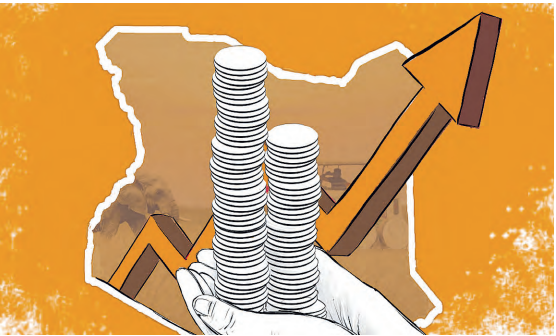

About 20 years ago, the figure that haunted Kenyan tourism authorities was South Africa’s 4.5 million annual international visitors.

As I recall, Kenya at that time had about 1.2 million visitors annually.

You can imagine then, just how heartbreaking it is for those charged with improving Kenya’s performance in this sector, that while we are only now at about two million annual international visitors, South Africa last year had more than eight million visitors.

We are definitely not “catching up”.

But this is not the worst of it.

Given recent trends, I have sometimes wondered if Kenya may soon have to consider how to manage with fewer tourists rather than how to get more of them to come visit.

I say this because certain cities in Europe, long considered as global “bucket list” icons, are right now contending with a phenomenon, which has been defined as “overtourism”.

Prominent among these is Barcelona, Spain, which apparently has 32 million visitors coming every year to a city, which has just 1.6 million permanent residents.

Current tourism policy in Spain is focused on how to ensure that fewer people visit Barcelona.

But there are other European cities which annually attract millions as well, including Florence and Venice in Italy; Dubrovnik in Croatia; and Amsterdam in the Netherlands.

Now if you are thinking, “We should be so lucky”, then you have not been to the Maasai Mara National Reserve during the peak wildebeest migration season.

To speak of the sheer number of tourists you will find at every key location of that park during such times as “overwhelming” is an understatement.

As a local, you stare at the many rows of land cruisers and other SUVs already in place, and the long convoys of other vehicles still coming, and you wonder if the visitors are really having “the experience of a lifetime” that they had been promised.

But this is where the conservancies come in.

The Maasai Mara and its famous wildebeest migrations are not the only reason why high-spending international tourists come to Kenya.

There are plenty of other natural attractions and other game parks.

Also, Kenya has a pretty good rate for return visits by tourists.

Many who have already been to the Maasai Mara, end up preferring a more exclusive safari, where they are not – effectively – caught up in a traffic jam, whenever a family of cheetahs or a pride of lions, is spotted near one of the access roads within the Maasai Mara.

And it is precisely such an exclusive safari experience that many of the conservancies provide.

I still remember how on a trip to one such conservancy just outside the borders of the Maasai Mara, I was at one point seized by the feeling that my little group in the safari land cruiser, and our guides, were the only people left on the face of the earth.

We drove for hours without seeing a single other human being, and not even any cows from the herds of the local Maasai community who were the actual owners of that conservancy, with the camp operators being their tenants.

So here is the odd thing about Kenyan tourism: While the French cannot make Paris (their prime tourism attraction, receiving about 40 million tourists every year) any bigger than it already is, when it comes to safaris, the conservancies have greatly expanded Kenya’s safari tourism potential.